By Dr. Greg Dussor and Dr. Ted Price

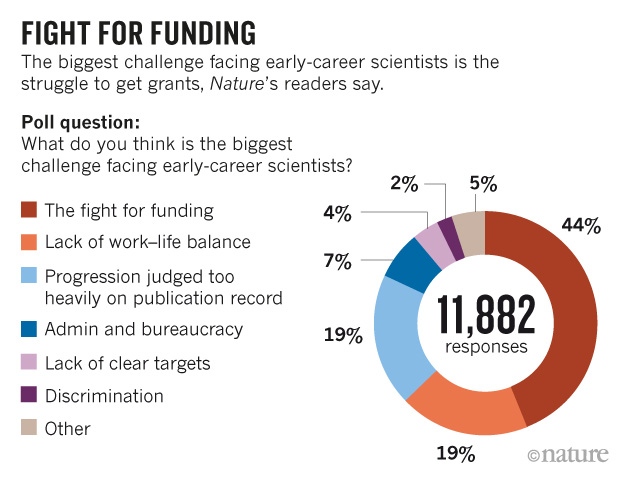

Being a tenure track faculty member is becoming more and more synonymous with becoming an entrepreneur and the CEO of a small business (your research lab). As such, you become solely responsible for raising funds for the operation of your new small business. However, unlike other entrepreneurial minded citizens that are able to solely focus on running their business, you are expected to perform a variety of other duties, such as, teaching, mentoring, creating social media content (case in point), spinning discoveries into marketable products, serving on university committees, serving as a reviewer for journals and serving on study section. So much serving! By the time you complete your auxiliary duties, you may be asking yourself, what time is left to run my lab and how will I raise money? According to a 2016 Nature survey, finding funding was cited as the biggest challenge for new scientists.

We have written the below five tips that we believe have aided us in crafting better grants and we hope that you find them helpful.

Tip 1 – Propose a project that you are enthusiastic about.

If you don’t like the project, reviewers won’t either. This is a common mistake that we both made in the past and see in study section. You may not think that your writing reflects your lack of enthusiasm, but when compared to other proposals that are written with conviction, the difference can be glaring.

Tip 2 – The aims page is critical.

Reviewers will often be ready to support the grant (or not) by the end of this page. This tip may seem cavalier, but it is rooted in the realities of the review process and reviewer workload. According to a 2019 report by Grant Review in Focus, “[F]unders spend up to 6-hours per application finding reviewers…and grant reviewers spend on average 10-days per year on reviews”. Time is limited and a written aims page is the grant equivalent of your elevator pitch.

Tip 3 – Ask for feedback from colleagues and take it seriously.

If you are colleagues see holes, reviewers likely will too. We know that everyone is busy, but academicians have tremendous resources available to them in their immediate colleagues. Asking for and seriously considering feedback from them will make you a better grant writer. Likewise, providing feedback to your colleagues will enable you to refine your reviewing capabilities.

Tip 4 – Think about the reviewer. They are reviewing many other grants. Make their job easy.

Use 1 figure per page, even if it’s a diagram of the hypothesis or experiment design. A wall of text is boring and intimidating. Including one diagram per page allows the reviewer to see a quick snapshot of the idea or data you are highlighting.

Tip 5 – Don’t propose overly complex experiments or too many of them.

It’s rare for reviewers to say there is not enough work proposed or that experiments are too simple. Traditional wisdom dictates that “simplicity is the ultimate sophistication” and when proposing experiments it is best to follow this dictum.

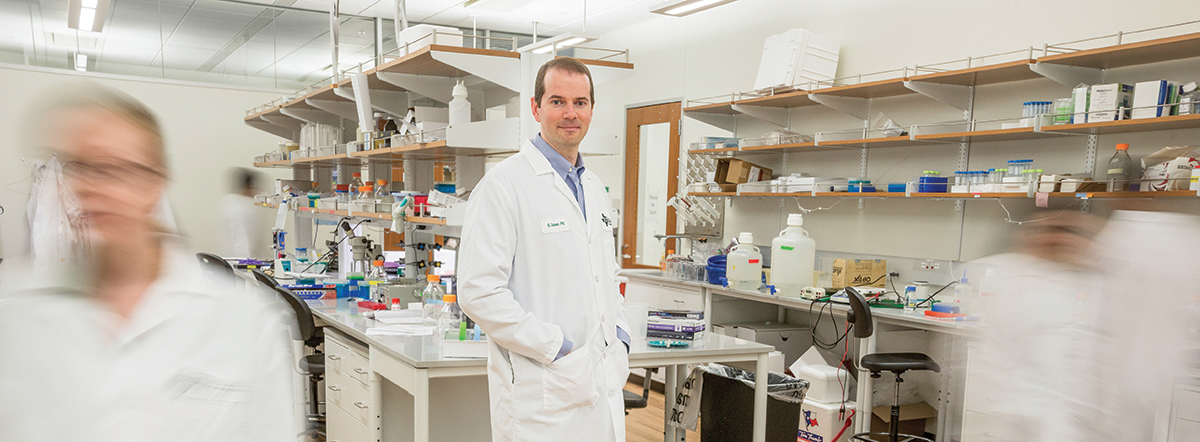

Dr. Greg Dussor and Dr. Ted Price have collaborated for the past 20 years. They have submitted countless grants and, in addition to private foundation grants, they are currently funded by five R01’s. Dr. Price teaches a grant writing course at UT Dallas and both Drs. Dussor and Price serve on NIH scientific review groups.